Idemitsu Art Award 2020 Grand Prix Winner Interview

I want to draw a new painting with the theme of “visible” and “invisible”

Idemitsu Art Award 2020 Grand Prix Shinya Imanishi

Established in 1956 with the desire to contribute to the development of domestic culture and art by providing a place where young artists who continue to create works every day can check the evaluation of their works, Idemitsu Art Award, a public exhibition sponsored by Idemitsu Kosan (trade name: Idemitsu Showa Shell), is now in its 64th year (49th year). The exhibition focuses on two-dimensional works by young artists under the age of 40, and has produced works by Jiro Takamatsu, Shio Suga, Asae Sotani, and Maiko Kasai.

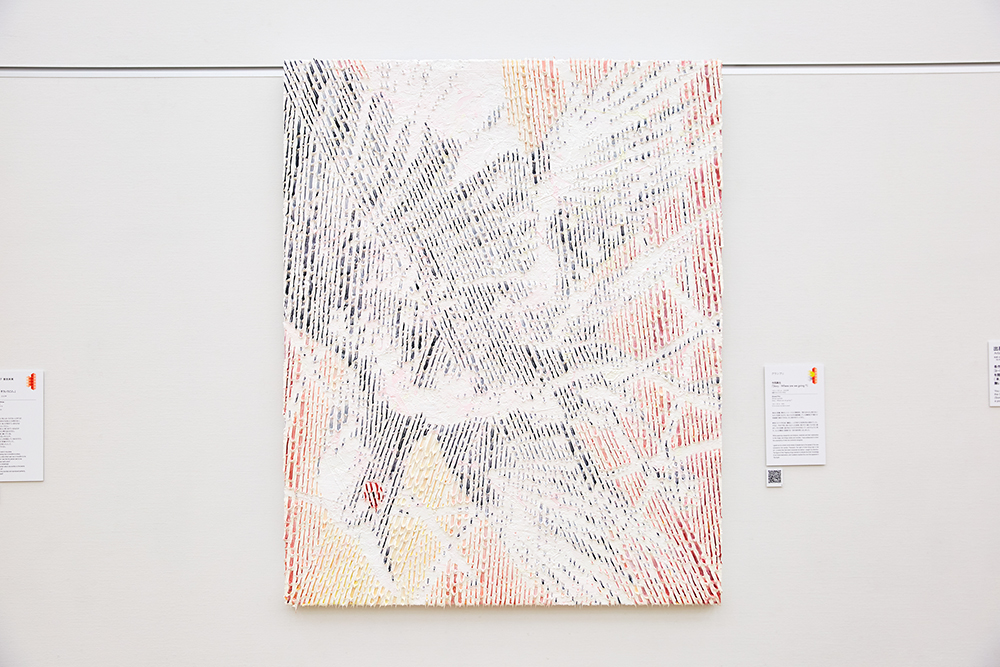

In 2020, Shinya Imanishi's “Story - Where are we going?” won the grand prize out of 846 entries submitted by 597 people. He is an up-and-coming artist born in 1990 who completed graduate school at Kyoto University of Art and Design in 2015. By changing the distance from which the viewer looks, the work looks like an abstract line painting or a silhouette of a bird, successfully combining the contrasting worlds of abstraction and fantastical images at the same time. Evaluated. We spoke to Mr. Imanishi about his motivations and process for creating the work.

Grand Prix winning work “Story – Where are we going?”

Developing unique techniques to create images in the mind of the viewer

─ Congratulations on winning the grand prize. What was your motivation for applying for this Idemitsu Art Award?

Due to the effects of the new coronavirus, scheduled exhibitions and commissions, including the Tokyo Art Fair in March, were canceled or postponed, and I was feeling discouraged, when a junior colleague of mine brought me an open recruitment flyer for the Idemitsu Art Award. He gave it to me. When I saw that, I thought it would be a good idea to take on the challenge at times like these, so I applied.

─ By the way, are you taking on any other competitions this year?

No, my work won't be understood unless people actually see it, so I won't submit it to a competition where I'm likely to fail in the photo judging process. Therefore, there are very few competitions that I can enter. Also, in many competitions, the thickness of two-dimensional works is stipulated to be approximately 10 centimeters or less, but my work exceeds that thickness. So, I never expected to win the award, and when I was told on the phone that I won the Grand Prix, I simply asked, “How many places did you rank?” (lol). I am truly grateful to have been awarded such a historic award.

─ For several years before the award-winning work, you have been creating works using a unique technique of carving away thick layers of paint.First of all, could you tell us about how you came up with this technique?

As I was exploring what it means for things to exist and what it means to see them, an art program I happened to watch on TV when I was a graduate student sparked an idea. The program introduced Hiroshige Utagawa's ukiyo-e woodblock print “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido” and explained that while Westerners at the time expressed rain with dots, only Japanese people expressed it with lines. It was explained.

At that time, I thought to myself, “Well, back in the Edo period, Japanese people were already able to connect dots and recognize them as lines,” and when you present them dots, they turn them into lines, and then they turn them into planes. I thought it would be a picture that could be recognized and completed in the mind of each viewer. By doing so, I thought it would be possible to create a state of “visible but not visible,” which I had been interested in for a long time. So, at first I was creating pointillist-like paintings.

─ From there, how did you develop a method that takes advantage of brush strokes?

I believe that a painting is, after all, a collection of actions. Through trial and error, I came up with the idea that by applying layers of paint and gouging them with a brush, I could leave a touch (brushstroke). Didn't you play with scratching the things you drew with crayons when you were a child? That's the feeling. I thought it would be interesting to draw a picture in which the points I was looking at come together to form an image, which then connects to other points, so I started experimenting with various techniques using my current technique.

─ How do you choose the motifs?

I choose things that remind me of the “next” thing that is drawn. I have drawn various themes that I would like to try, such as using thunderclouds as a motif to suggest the next movement, “It looks like it's going to rain,” or using candles to express light and time.

Shinya Imanishi Born in 1990 in Nara Prefecture, lives in Nara. Graduated from Kyoto University of Art and Design in 2015, majoring in artistic expression. Currently affiliated with nca | nichido contemporary art. Major awards include "Kyoto Art Tomorrow 2019 - Kyoto Prefecture New Artists Selection Exhibition" (Excellence Award) and "3331 Art Fair 2015" (Hideo Tanaka Award, Junya Komatsu Award). In recent years, he has held exhibitions both domestically and internationally, including in South Korea and Taiwan.

In a digital society, I want to create paintings that can only be understood by actually seeing them.

─ Please tell us about any new challenges you faced with this Grand Prix winning work.

I am taking on the challenge of how to express the story without directly mentioning the theme, which I have been thinking about for some time. Around spring, when the coronavirus outbreak began, I saw flocks of crows in nearby places and on TV, and that caught my attention, so I used Yatagarasu, which symbolizes guides in the Kojiki, as a motif to express the idea of “this era.” I drew it with a theme that makes me wonder, “Where are we headed?” However, it could be a bird that the viewer imagines, or an image of it “flapping its wings,” and I would be happy if the viewer could think of the story themselves.

─ This work seems to have a high degree of abstraction. The judges also said in the catalog that at first it looked like a linear abstract painting.

I agree. I painted it so that it would look like an abstract painting depending on the viewing distance. I always start with drawings, but for the bird motif, I first drew about four images that I had in mind, then I printed them out and pasted them on the wall, and when I looked at them from a distance, I drew them in the most vivid way. I made a nice picture of it.

─ There are unevenness caused by the paint, and I can't help but look at it from the side of the canvas. Could you tell me the general process of how it is created?

First, I painted over the crow motif as shown below, and then covered it all up with brush strokes using white paint. He then lowers his brush to the white screen and makes a gouge, but the tip bounces back as if defying gravity, repeating this motion. To be honest, it's fun for the first three minutes or so, but after that it's like copying a sutra (lol).

─ I was surprised to hear that you drew the diagram below carefully. It seems like it would be hard to maintain motivation if I killed it and started drawing again.

I've drawn it at least three times. Once I have a rough sketch, I think to myself, “Now what will happen!?” and dive right in again.

─ How long does it take to draw one piece?

This work took four or five days to prepare. I prepare a panel or canvas, calculate the amount of paint needed for each color, and save up a little extra and put it in a pile. However, after about 5 days of starting the painting, once the surface of the paint dries, it becomes difficult to gouge, so I finish the painting in about 3 or 4 days.

─ What is the most difficult part?

I take a picture of the lower part of the drawing, import it into my computer, process it into only dots and lines, project it onto the canvas, and then gouge it out with a brush, but I don't know where or how the lower part will come out. There is also. For example, I was a little worried about whether I was carving the edge of the beak or the edge of the wings, but I kept digging until the end.

─ It seems like it's a race against time and it won't be possible to redo it, but is it possible to fix it? How do you make that decision?

I'm desperately trying to make sure that the brush strokes and the underlying layers come out comfortably, so when they're off, I can tell by the discomfort. Lately, however, I've come to think that it's interesting to have a lot of coincidences, where things fall apart and fall apart.

─ How do you decide the thickness of the paint?

It's getting thicker every year (lol). The thicker the brush, the more it feels good to create an edge when you gouge it. I also wanted to make sure that when viewed from the side, the part that bounced back would look beautiful.

I also think that the sense of distance is an interesting thing that humans have, and I want to make paintings interesting whether you look at them from a distance or up close. To achieve this, we use a variety of techniques, including not only gouging, but also creating fine horizontal lines with a comb and adding dripping.

Even in this digital age, I believe that paintings are more enjoyable when viewed directly, so I want to create works that allow you to feel this, works that you can't understand until you actually see them.

Balancing the 4th generation of a long-established Narazuke store with artist activities

─ Going back to the story, when did you start drawing?

I have always loved drawing since I was in kindergarten, and by the time I was in junior high school, I was thinking of going to an art university. Ever since I was a child, I've wanted to see a world I've never seen before, and when I saw Rene Magritte's “Empire of Light,” I thought that if I painted a world I'd never seen before, I could see it. is.

Actually, my parents' family owned a pickle shop in Narazuke, and I wanted to go backpacking when I grew up, but I also knew that I had to take over the family business, so I thought it would be impossible to leave the house for two weeks. . However, I wanted to do something else besides work at the family business, so even as a child I thought that I could do both by becoming a painter and painting on weekends. So, with my parents' permission, I entered Kyoto University of Art and Design.

When I was an undergraduate student, I studied academic painting and drew, but in graduate school I met Tatsuo Miyajima, Noboru Tsubaki, Daisuke Ohba, and Shigeo Goto. When I was an undergraduate, I had read about Gerhard Richter and learned about him, but I didn't really feel a connection to him, but once I understood how to look at contemporary art, I instantly connected with him. did. Then I actually went to see things like the Frieze Art Fair in London and the Basel Art Fair in Hong Kong, and I thought, “Ah, this is what it's all about” and it made sense to me.

─ When you say “this is what it is”, does it mean that you now understand contemporary art, or does it mean that the act of drawing has become more serious?

It's both. In graduate school, I re-studyed the history of modern and contemporary painting and learned how artists create concepts and create works.

After that, I went to the Frieze Art Fair and was impressed by the size and high quality of the works by Gerhard Richter, Jeff Koons, and other artists from Galerie Perrotin, and the large space in which the customers admired their works. I was impressed by how gorgeous it seemed. It made me realize that I had to think more about it when I created it. From then on, my style changed considerably during my two years at graduate school.

─ How do you balance your work as a painter and your work at Narazukeya in your daily life?

After graduating from graduate school, I was fortunate enough to be invited to participate in exhibitions, so I got busy with production, so I got up at 7 a.m. and made sure that my part-timers were ready to work by about 10 a.m. After that, I work in the studio until about 7pm, and then go back to work at the shop in the evening.

─ By the way, Mr. Imanishi, what kind of work do you do at the Narazuke store?

The shop was founded at the end of the Edo period, and even today they continue to make their products using the same Edo period methods without using any chemical ingredients. The color and shape are different from the common Narazuke. I also mix the sake lees for pickling, and I also think about the composition of each ton to make it a certain color. Maybe that's why there's so much paint (lol).

I thought that painting, which requires constantly creating new things, and narazuke, which requires continuing to create the same thing for 100 years, were somehow different, but I thought they were somehow connected through one person. I think now. 100 years doesn't feel like a long time, and your sense of time may be different from those around you.

─How do you plan to continue your production activities from now on?

People who have seen the exhibition so far have said it's nice, but not many people knew about it, so I'd like to increase the chances for people to actually see it. With the theme of “visible” and “invisible”, I would like to try out the evolution of this work and new methods. I tend to think of myself as stoic, but there are many works in my atelier that I create for fun without presenting them to the public. First, try it with your hands. After all, I want to create something new.

Text: Yuri Shirasaka / Photography: Maki Kato / Editor: Toshihiro Horiai (JDN) / First appearance: Contest information site “Toryumon”